“I am out with lanterns, looking for myself.” – Emily Dickinson

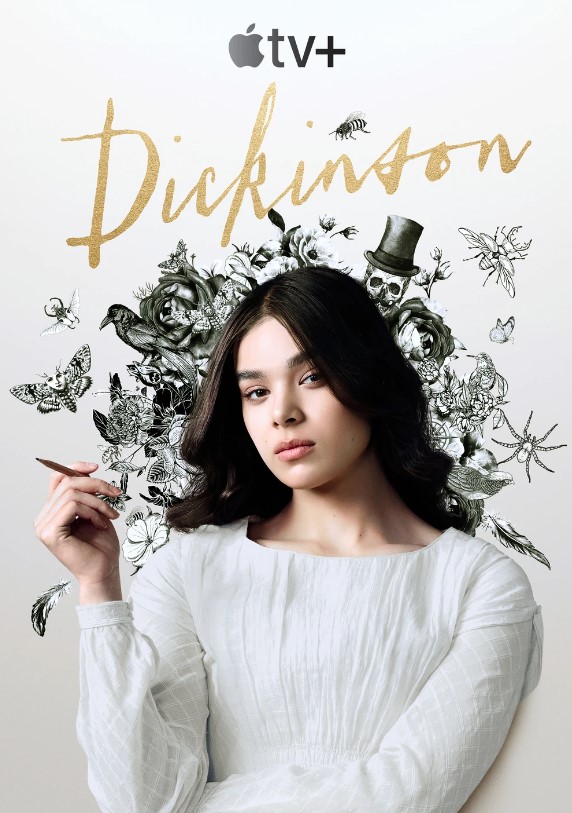

I am always a sucker for a good, literature-referencing movie, show, or piece of media. I am, however, also chronically late to every cultural event as is happening, save for Bridgerton (2020) on Netflix. So, while the show has already been canceled after several seasons and smarter people have given their opinion, it’s time for a less educated and less timely take: Apple TV’s Dickinson (2019). I tried to watch it in good faith for about three episodes, then I admittedly jumped around and skipped through whole plotlines to find the guest stars. I loved the manifestation of Death portrayed by Wiz Khalifa and Zosia Mamet as Louisa May Alcott. Even John Mulaney made an appearance as Henry David Thoreau. Yet I couldn’t help feeling throughout the show that it would have been stronger as an almost sketch-comedy, wherein certain historical figures are lampooned against their stereotypes and historical characterization – School House Rock or Liberty Kids, but with a distinct 2024 flair. Something completely irreverent as well such as Oh, Mary! (2024), a dark comedy about the lives of Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln, which has little historical weight and is a purely fun romp. Yet I found this show harder to enjoy and I was curious why I couldn’t just find it funny. Why couldn’t I just love the show for its theme song, “Afterlife” by Hailee Steinfeld? (Which is a song I loved). It’s a song I’ve cried to, in fact, for reasons unimportant.

It was the character of Emily, played by Steinfeld herself, who possessed an anachronistic modernity. Yet not in that way that we condescend when we speak about historical women in the past by saying she was a “modern woman,” as though women have not been interesting or strong all along – but what people think they mean when they say she was “ahead of her time.” Emily Dickinson, beyond all doubt, was surely of her time. While there would have been conveniences that would have made life longer, easier and happier, I do not want to imagine what my life would have been like so many years ago. My own personal sign of whether I think a piece of historical fiction is good is when I think to myself, “If only they lived nowadays and could divorce their terrible husband!” Unfortunately, most historical retellings tend to smack of whatever cultural morsels were consumed at the time of their creation, and this is certainly the case with Dickinson. It can show up in places like vernacular and vocabulary (i.e., swear words), PDA, and even in makeup, especially. YouTube is packed with fashion historians who can breakdown character appearances based on whatever was fashionable at the time of the film production rather than the actual period it portrays. You can tell that Doctor Zhivago (1965) was made in the 1960s because of the tan glow of the characters year-round, the big hair on the female leads, and the pale makeup on the lips with the intense makeup around the eyes. You can tell that Titanic (1997) was a movie from the 1990s because of the starkly red lipstick and arched eyebrows, while the mainstream makeup of 1912 would have had more of a smudged look around the eye, with eyebrows thin and penciled on. It might be tolerable, and even entertaining, if Emily Dickinson used contemporary swear words while railing against the rights of men to pursue intellectual endeavors (in a monologue to her sister-in-law/best-friend/lover). Yet it carries a sentiment that falls flat yet again, given the reality of her known life. Emily Dickinson did go to college for a brief time at the Amherst Women’s Seminary in Amhurst, Massachusetts. In fact, there are women now who, due to various social and political blockades, are discouraged from obtaining an education. Shouldn’t we be turning our hearts and attentions to them?

These stale platitudes, rehashed throughout the show, concerning “why women go to the lectures” hold no water. The character of Emily feels like she has been dropped into the 19th century directly from the 2000s and everything must be explained to her all the time, like a time-traveling tourist. (If you want to watch a show where this is the actual premise, I recommend the 2008 television mini-series, Lost in Austen, wherein a woman named Amanda from the 2000s swaps places with Elizabeth Bennet’s regency-era existence). The real Emily Dickinson would already know these rules. This is her world, not ours. Genius, kindness, and genuine wisdom are traits that are always shocking for their time because we as human beings live in a world that has always lacked such things; that is why Emily was radical, not because she was willing to put her hands on her hips and complain about the state of women. She never preached that women possessed or needed an inner life; she simply had an inner life which she was bold enough to put down on quill and paper – the page being the only thing that can last. In the show, Emily’s father is seen and heard hating her writing, yet there is no context as to why he thinks it’s unworthy of her time other than that he doesn’t want his daughter to work outside the home. In fact, not only were her instructors impressed with her talent for composition, but they also praised her skills as an amateur botanist. Dickinson had a large assembly of pressed plants (or herbarium) which she arranged and archived, along with their accurate, Latin names. Emily’s mother’s concern over the household is seen as something to be scorned: a filmmaking cliche. Domestic self-sufficiency is scoffed at generally within the narrative and the notion of women’s work being lesser is something that trapeses through the episodes and generally left me irritated. To be fair, the character of Emily does at one point make a loaf of bread as thanks to her father, but other than that, considers most, if not all things, beneath her. “Sometimes I feel like a slave” is a truly bombastic claim, which Emily raddles off in Episode 1, Because I could not stop, especially when one considers the plight of those in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, for instance, with the terror of African American slavery reaching its zenith before, during, and after Emily Dickinson’s time. The past is not always worthy of our nostalgia, but we must acknowledge it. While the past is not sacred, it happened, and despite all its versions; it is true. Truth can only be altered so many times before it becomes a parody of itself and a form of saccharine wish-fulfillment.

Period dramas like Dickinson tend to make explicit the implicit, and in a highly distracting manner. In reaction to queer-coded characters and subliminal messaging throughout 20th century media, the pendulum has gone completely the other way. A character cannot merely exist as a gay person, we are now compelled to tell the audience that a character is gay or have another character say it for us to be sure a character is, in fact gay. It seems characters are not allowed to live in the subtext of anything anymore. It was apparently not enough to let Emily Dickinson’s famous words resonate from her historic correspondence with her intimate friend, Sue, “I tore open your letter and licked the envelope’s seal for any lingering taste of you,” – we, in our ignorance, required an entire sequence wherein the characters Emily and Sue run off to the woods and share a passionate, open-mouthed make-out session to the tune of “Be Mine – Jaakko Eino Kalevi Remix” by Alice Boman. To view her with a lens of being nothing more than a wildly closeted lesbian also discounts the deeply romantic letters between her and Otis Phillips Lord, a Massachusetts lawyer and politician who was suspected of being a lover of Emily Dickinson later in her life. To create a smoother and “stronger” characterization, Emily is completely stripped of all the parts of her that would be too complicated to explain. The choice between Sue marrying Emily’s brother, Austin, and being romantically involved with Emily herself is made out to be a plain decision for Sue, but it wasn’t. Had Susan not married, she would been resigned to the Workhouses or any number of socially taboo professions common to 19th century America, such as a sex-worker.

We can and do investigate the past, but we must take off the lenses that we wear when we do. These modern filters tend to make the past seem farther away than it was. The real Emily Dickinson did go to college, despite what the show may have proposed, and she hated it, wishing to be home instead. Historical fiction should highlight something of the past, brushing away the stone surface of a gravestone to reveal the letters. Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace, both the series and the novel, marvelously reveals how dangerous life was for women and how Grace feared for her life everywhere she went. It demonstrated how men’s desires, sexual and otherwise, constantly put women in danger. No matter what would have happened, it would have been the woman’s fault. It doesn’t matter that Grace’s friend was a maid and that the owner of the house’s son was considered a gentleman. The power imbalance was so skewed in his favor. Grace was the woman and her death at the hands of a botched abortion was somehow her own fault – or at least that’s what everyone around Grace implied. Jodi Picoult’s novel, By Any Other Name, also gave a sense of how impossible it was for women to be writers during Shakespeare’s time and how the odds were so stacked against women like Emilia Bassano, that it was a miracle she could publish anything under her name. The stakes were simply different. This is the problem with attempts at historical fiction like Dickinson: we place these characters in the past with contemporary sensibilities and stakes. The stakes of crossdressing during that time don’t seem too bad if all that happened was a gentle scolding, when in reality they would have been liable to be arrested, had they been caught. Crossdressing laws were in full effect in Emily Dickinson’s time and were often grounds for people being admitted into insane asylums. For instance, in Columbus, Ohio, where one of these earliest ordinances was enacted, an 1848 law prohibited a citizen from appearing in public while wearing “…a dress not belonging to his or her sex.” As such, an episode centered around Emily and her friend Sue disguising themselves as men to gain admittance to a public venue fell flat (Episode 2, I have never seen volcanoes). Emily was a character who functioned as though there were no stakes to her rebellion whatsoever, other than her father being cross with her at dinner.

Emily, the character, seems unwilling to engage in the day-to-day sacrifices and compromises we all make, regardless of gender. Which in fact also paints her as a bad poet, as it makes her someone who is unwilling to step outside of herself and desires, when we know that the woman of Emily Dickinson was a marvel. She felt things terribly deeply, to the core of herself, and her bravery may not have looked like much to us in the present day, but it was everything. She was an attentive daughter, sister, and aunt.

She was highly introverted – even reclusive, some have said – with an almost mythic, inner life. Her poems defied expectations of the time by rarely having titles and featured bizarre punctuation and capitalization conventions which proved challenging for critics to understand yet revealed a mind that was devoted to her own, inner code. She wrote because she had to, not to impress or to have literary fame. “I love it when people quote me,” so says the character of Emily in the television series. I had little strength to not roll my eyes, especially since much of her work would not be discovered, let alone available to the public, until after her death in 1886 – when her younger sister, Lavinia, started to become obsessed with seeing Emily’s 40+ notebooks and loose sheets published. According to scholars, Emily Dickinson chose to stay within her family home for most of the time in her late twenties instead of venturing out into the world around her. She was rarely reported to travel and seemed to base her perceptions of her friends on their ability to respond to her letters. Emily Dickinson’s iconically shadowy and elusive spirit is sacrificed for visual and physical indicators of rebelliousness that can be appreciated by a streaming-service audience. But the extroverted nature that tends to run through modern day feminism need not march over the quieter, humbler voices of feminine history. Odd women can make history. Scared women can make history. Isolated women can make history too.

By all accounts, Emily Dickinson may have lived in the implicit and the subtle, but we can love her with an explicit love. We do not need to remanufacture her entire character to appreciate her spirit. In doing so, by producing a power-washed, pre-packaged Emily Dickinson, we eliminate the woman inside who had the tender genius to say, perhaps whisper, her immortal words: “I dwell in possibility.”