In the last few moments of the film Hemmingway and Gellhorn (2012), we see and hear Martha Gellhorn, the famous 20th century war-correspondent and third wife of Earnest Hemingway, tell her editor over the phone, “Its Gellhorn. I’ve decided to go after all. Why? Because as usual The [New York] Times got it wrong again. All that drivel, that goddamn objectivity shit. I’m going to be on the next plane. No? Well, goddammit, I’ll pay on my own dime. I can’t wait for you to grow a pair of balls. You relax…” After hanging up she looks to the window.

“I’m not dead yet, you fuck,” she says to the crow who, moments before, had been tapping on her window. I love that line. It was a callback to earlier in the film where we are told through the visual language of ravens, sepia tone, and Hemmingway compelling her to “get in the ring,” that Hemmingway was the one who inspired her, with the pair constantly having a similar go at other writers of their time. Even if their love for one another did not survive; their love for the truth did. Gellhorn is mentioned in passing within Monsters by Clare Dederer. She would have wanted it that way. She never wanted to be known as ‘Hemmingway’s wife.’ It’s hard to know if she got her wish. In war correspondence circles, she was a force of her own, a hurricane. She was the first reporter on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, smuggling herself onto one of the ships in a nurses uniform. In literary fiction circles, she is known as the only woman who left Hemmingway. Life and influence are about perspective. Hemingway is mentioned in Dederer’s text extensively, both in his genius and flawed humanity. According to Dederer, the writer Martha Gellhorn didn’t think the artist needed to be a monster; she thought the monster needed to make himself into an artist.

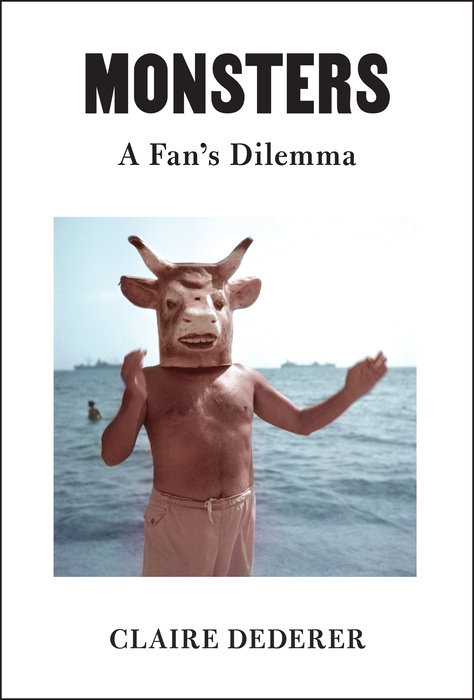

“A man must be a very great genius to make up for being such a loathsome human being.”[1] Many monstrous men are loathsome human beings. Women are as well, though not enough for Claire Dederer or my own liking. (See her chapter on Abandoning Mothers). Few women have been given the license to act monstrously in society outside of cautionary fairy tales. It is one of the things Dederer makes us wonder about in her book. Where are our feminine monsters? Why are there not more? What is the perspective we may be putting someone into where they either do or don’t belong? Monsters is a work about feeling – what we feel, why we feel, and how we feel. To approach society’s creative monsters with logic implies a “moral calculator,” to use Dederer’s words, when there isn’t, or at least not one fine-tuned enough to consider every experience. What we feel becomes legitimized on her pages, becoming its own sort of individual theology.

Religiously speaking, feelings operate in a strange way, as does perspective. We are meant and encouraged to trust lofty feelings, feelings that get us out of our body, almost like floating. Things like serenity, which I discovered the author Joan Didion always associated with death, are encouraged. It’s something that removes us from control of our feelings and can be encouraged as well. Depending on the church, one is allowed to be moved by the Holy Spirit, within reason. Speaking in tongues is also allowed. Demonic possession though had to be rid of because that was the wrong surrendering. Whether one invited these demons is up for theological debate. Passion for the Lord was alright; passion for a boy had to be resisted (ironic considering our Lord Himself became a human as the Christ figure, craving the subjectivity of existence despite living a completely objective one, per the Christian myth). Disgust for humans is discouraged, but disgust for the dreadful things humans did is encouraged. It felt like there was no way to be a human without keeping the score or without wondering if one had let themselves get too far ahead. There are right feelings to be had and wrong ones. So, we try to be stoic, yet without much success, considering we are not able to weigh life correctly or be objective enough. This is something we feel instinctually, especially when we are tasked with trying to vilify or nullify the ‘monsters’ of the world and the art we make.

What’s love got to do with it? Everything.

That is what I thought of whilst reading Monsters by Claire Dederer, which has easily become nestled into my top ten favorite books of 2023. Validation of perspective is the gift of Dederer. Getting rid of the ‘objectivity shit.’ Because that’s what it is: bullshit. We mock ourselves by pretending that our own lives are not the baggage we bring to art. To use a word that Dederer uses herself, the actions of artists do ‘stain’ their art. Give yourself permission to take weeks with this book, make notes, watch Midnight in Paris (2011), let yourself be disappointed, and let yourself be lifted up as well. Be moved and be immovable. The tension of being human is learning how to live in the spaces between – between a million things, between you and the world, between you and whatever deity calls your soul, between the questions and the answers. Of course, questions are more important than the answers and to quote Andrea Long Chu when she was featured on the podcast High Low with EmRata, “It is the critic’s job to tell people how to think, not what to think.” Dederer is telling us not only how to think, but giving us permission to tell others. Feeling is the body’s way of thinking and weighing; it is how we live. You cannot live someone else’s life for them, Barbie’s Princess and the Pauper (2004) notwithstanding.

You can also not love someone else’s passion for them. You cannot clean out a stain of someone that you did not create, nor is on your own clothes. We must forgive one another, though not necessarily these people, even if their crimes did not happen to us, but we must forgive one another for our problematic favorites. If we cannot forgive one another then the monsters win because their stain will then spread to the ones we love and respect. We will equate the appreciation of Annie Hall (1977) with approval of emotionally grooming one’s girlfriend’s daughter, which I doubt any of us are secretly aching to do. The truth is that these men have made things which made us feel human, seen, and understood as well as accepted. It frightens us to identify ourselves with them at all, but just because we see that the monster has eyes like ours doesn’t mean that we now have horns. To paraphrase the brilliant Azar Nafisi, to understand doesn’t mean that we condone. Would it not be as important to understand where the monsters came from? As uncomfortable as it is, there is less separating the monsters from us. At the same time, others would ask me to juggle. Is it incumbent on us to understand them? Victims are often, repeatedly, being asked to be understood, while we ‘understand’ monsters without little forethought or stress. They are begging to be considered. Selfishness of the artist is given space to breathe as well. Working mothers and women may not be monsters as we think of them, but there is an inherent selfishness to the notion of making art and being asked to be alone with that art. All these concerns are brilliantly articulated and given space by Claire Dederer.

She balances and considers in ways that will quiet even the most pedantic “well, actually” observer from the crowd.

As I write this, a picture of my mother and myself stares at me from my writing desk. I wonder how much of this my own mother felt. She was a writer, editor, and translator. I wonder how monstrous she allowed herself to be. Perhaps too much, perhaps not enough. Is the answer to all of this in Monsters?

“What do we do about the terrible people in our lives? Mostly we keep loving them…When I was young I believed in the perfectibility of humans. I believed that the people I loved should be perfect and I should be perfect too. That’s noy quite how love works.”[2] In the end, the answer is unsatisfying because life is unsatisfying. Why do we love these works and these men? Because we love them; we love them both, like the neglected child who loves his mother even after years of therapy. Like the scorned and thrown-about wife or like the boyfriend who never told us they loved us. We love them anyway.

Love is not rational or something that can be ushered away with facts.

It is love. It makes us hypocrites. It makes us interested.

It makes us human.

[1] Dederer, Claire. Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma. 1st ed., Penguin Random House, 2023. p. 174.

[2] Dederer, Claire. Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma. 1st ed., Penguin Random House, 2023. p. 256.